The aim of my collaboration with Tough Dough’s Message Sent, was to complement and contextualise the creative exchanges that evolved out of the project. By exploring the potential of dialogue in all its forms, the intention was to develop an opportunity to examine how the experience of living through a national lockdown had impacted the lives of artists/makers and their practices and where such a challenge had led them. At the heart of this endeavour lay the desire to critically analyse what healing and recovery through making really means and looks like to those who embark upon such a journey and how that trajectory might shape and engender new points of creative departure.

Tough Dough

Message Sent

Collaboration:

The Power of Creative Exchange

(This is an extract – the full essay can be found here)

During the initial stages of the pandemic, the isolation, fear and the instability of an unknown future, emphasised the need for collective engagement and solidarity, if nothing else but to reinforce a sense of survival in the face of what felt like an uncontrollable dark force. Across the globe, creative collaborations formed, some investing in and expanding upon their pre-existing networks, whilst others evolved from less formal beginnings through friendship and shared practice; it was from the latter that the Message Sent collective grew and established itself amidst the turbulence and trauma of a national lockdown.

Message Sent combines a plethora of collaborative experience, both nationally and internationally, with that of individual studio practice. It was this collective vision that inspired four artists living and working in the Penwith peninsula in South West England to form an alliance with four artists living and working in North East England. Through forging creative bonds, they expanded their practices both individually and collectively.

Art history, as curator Ellen Mara De Wachter states, has “glorified the individual (usually male) artist as the ideal type. An alternative art history would involve an account of the constant interplay between the individual and the group” whereby collaboration and individualism continue to be “two sides of the same coin”.1 It is the latter that is pertinent to Message Sent, which is as much about the individual as the group. Collectively Message Sent is multidisciplinary, each of its eight members working within and across the fields of community arts, sculpture, painting, photography, film, performance and writing through interaction and dialogue. Message Sent defines the essence and meaning of its collaborative quest through creative practice itself and the transformative relationships between its members.

Message Sent is by its very nature non-hierarchical and its leadership collaborative, making way for creative practice to play out across a network of possibilities, forming a myriad of conceptual threads – meeting, diverging and reconnecting to form a mycelium of fruitful perceptions and interpretations sometimes through intuition and at others through happenstance. Its driving force is not just a psychological state of commitment to work towards a group goal, but an appreciation of the value of the qualities, desires and needs of individual members as equal to those of the group as a whole. It is this humanist belief in individualism that gives Message Sent its creative momentum.

There was a collective need to quench a thirst, break new ground, take risks and in doing so foster a dynamic of mutual support and innovation – for as they themselves declare “you cannot pour from an empty cup….”. 2 Their work embraces a particular kind of creative sustenance through the ebb and flow of reciprocal exchange – reconfiguring trajectories of creation, inspired by anticipation, expectation and revelation. It seems that humans can survive and thrive better by working together and in this sense, Message Sent plays a principal role in maintaining the creative resilience and emotional wellbeing of its members, engendering a form of presence in absence, in a world suspended in isolation.

With its focus poised upon creative process and exploration, ideologically, Message Sent is not interested in a fixed end product (art object) or the trappings of public scrutiny and consumption. Each of its individual members traversed and collapsed time and space both virtually and metaphorically through social media platforms and the unfolding trajectories within both imagined and real landscapes, embodying rather than disembodying presence in absence.

Gripped by the concerns of the pandemic, Message Sent members welcomed the move back to their own studios, despite its initial challenges. As natural collaborators many had nurtured the creative development of others through differing narratives and community projects for many years, whilst others had had to prioritise family and work, leaving little time for studio practice. The first set of postal exchanges were about their initial reaction to the Covid pandemic lockdown. These exchanges were like gifts, beautifully constructed and carefully packaged with love and empathy and became powerful tools to support and reassure during uncertain times. These small-scale artworks are imbued with a particular kind of emotional significance, but whilst they deepened the emotional connections between the individuals within the group, they also incited excitement and awe.

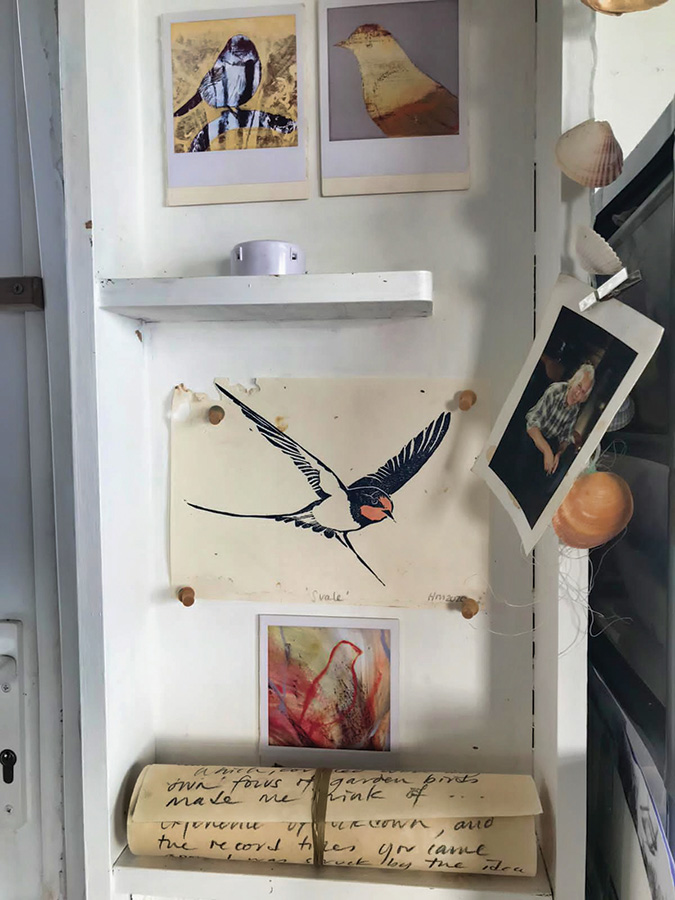

The initial constraints of the lockdown induced a strong need to impart a sense of hope and freedom. John Keys’s images of garden birds alighting are an expression of weightlessness and the embodiment of freedom itself. Accompanied by a recording of Bob Marley’s Three Little Birds, “Don’t worry about a thing, ‘Cause every little thing gonna be all right…” an anthem of hope and freedom, they symbolise a form of liberation, which when received by Nicola Balfour were turned into a shrine, to which she added her own objects of personal significance.

In his paper ‘Touching the World – Vision, Hearing, Hapticity and Atmospheric Perception’ the Finnish architect Juhani Pallasmaa emphasises the importance of the relationship between touch, vision and hearing,3 which generate sensory sensations and can trigger deeply felt emotions. This could not be more evident than in the exchanges between Sharon Bailey and Alessandra Ausenda, which through their tactile beauty invite one to touch and hear imagined voices, drawing attention to the importance of listening, being heard and cutting through the silence of isolation.

Sharon had done a lot listening during the lockdown while talking to people in care homes; this prompted Alessandra to create her assemblage of stone ears, nestled in the palms of nurturing hands, emerging from the soil as if the earth itself was listening. Her delicate cast of an ear, like an ancient Greek relic rescued from a ruin, sits in a box, cushioned by a concertinaed text, where partially visible words whisper between the folds.

Sharon’s origami Chinese thread book, It was the Best of Times, It was the Worst of Times, with its folds beautifully crafted with tender care, although inscribed with happiness at having time to reflect in nature, equally expresses her deep sadness about the grief that unraveled around her. The coal rubbings within, created from sea coal from her beach of comfort, beauty and space, echo how the tide made its own coal drawing along the edge of the shore. The single shell within whispers the words ‘I hear you’ like Sharon’s recorded whisper, Things I’ve been Told this Week – and her film Covered, which are poignant portrayals of old age and isolation during the lockdown.

It was the experiences of and responses to the natural and home environment that became the cornerstone of the Message Sent narrative throughout the lockdown. Through a series of dialogues, it became evident that trust influenced the exploration of undiscovered creative territories through investigation and experimentation. Message Sent made room for individual as well as collective playfulness, humour, tenderness and theatre through intimate exchanges of alchemic imaginings. Within domestic as well as outdoor natural spaces the quotidian and imaginative worlds formed a chiasma. The ordinary became extraordinary and the warp and weft of the everyday and artistic practice constituted the fabric of life itself, balancing individual desires with a collective commitment to a creative dialogue of stimulus and response. The time and space of the lockdown afforded a reflective meditation upon the creative act itself.

References

1 De Wachter, E. M. (2017) Co-Art: Artists on Creative Collaboration, London: Phaidon, p. 6

2 Message Sent, (2021)

3 Pallasmaa, J. (2017) ‘Touching the World – Vision, Hearing, Hapticity and Atmospheric Perception’ Invisible Places 7– 9 APRIL SÃO MIGUEL ISLAND, AZORES, PORTUGAL, p. 22