In 2019 Amanda Lorens produced a single screen video, Under Darkness, followed by a video installation Night Song in 2020. I was very interested in how Amanda had captured the trauma and enigma of insomnia with such poignance and evocation based on her own experience.

Thoughts Fall Like Raindrops

Thoughts Fall Like Raindrops

Imagine staring into the darkness, with a yearning to fall into a deep and restorative sleep, with no hope of doing so, or waking too early in the dead of night to the fear of diminished chances of slumber, whilst twisting and turning, in an attempt to stop the mind churning. Perhaps hours have been spent perfecting the art of distraction, whilst exploring many a potion in pursuit of an ever-elusive good night’s sleep. Both the acute and chronic forms of insomnia are very common, roughly, 1 in 3 adults worldwide have insomnia symptoms.[i] So what happens to the insomniac in the depths of the night – where do they go in their mind’s eye? By way of her single screen video Under Darkness, 2019 and her video installation Night Song, 2020, Amanda captures the trauma and enigma of insomnia with a cognizance, born of experience.

There is something anthropological about Amanda’s practice, both past and present. She has often collected and restaged the experiences of her subjects, questioning notions of why and how their individual perceptions and behaviours have been influenced by their environment, social interactions and conditioning. The research for Under Darkness and Night Song, which involved gathering the psychological and emotional thoughts of those suffering with insomnia, was no exception. With this her raw material, Amanda crafted a phantasmagoria of the conscious and unconscious sleep starved mind. In many ways Amanda’s practice is not unlike that of the late Susan Hiller who was once described as an ‘archaeologist of the unconscious of our culture’.[2]

Where Amanda’s Under Darkness and Night Song, explore both the impasse and the liminal energy that is generated in the space between anxious wakefulness and sleep, Hiller’s Dream Mapping, 1973, attempted to bring dreams from the outskirts of the known world into the centre of our consciousness.[3] Just as Amanda strives to make that which is hidden, visible, depicting the subjective as universal, Hiller too attempted ‘… to erase or erode the supposed boundary between dream life and waking life… making visible, that which has been rendered invisible’.[4]

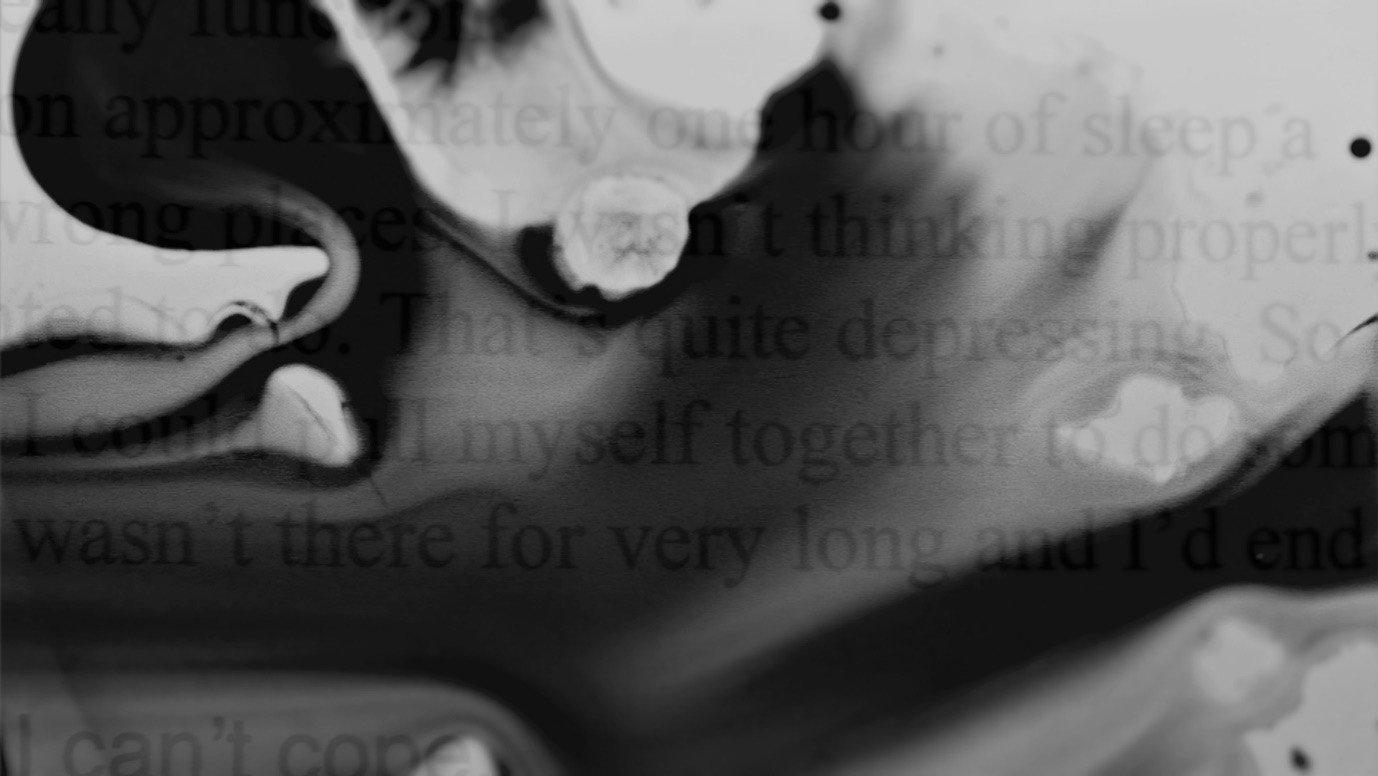

Night Song – Painted film still, 2020. The eye we see emerging from a subliminal oceanic landscape, in both Under Darkness and Night Song, is not only the subjective eye of the artist, but the universal eye of all who view it.

Both Under Darkness and Night Song offer us an opportunity to immerse ourselves in a phenomenological encounter where our focus is brought back to our own body as a site of subjective consciousness and sensory perception. Our vision moves across the surface of its object at close range rather than plunging into illusionistic depth, thereby privileging texture over form.[5] Images become tactile when they foreground textures in this way, exposing their physical and material qualities and creating a rich sensory overload.[6] Amanda exploits this through the materiality of her chosen media, and its interrelationship with the visceral qualities of music, sound, the spoken word and the fleeting connotations of printed text. Using stop motion animation, she creates an inseparable intertwinement of vision and touch. The monochromatic nature of both Under Darkness and Night Song reveals the structural emphasis of each image in an abstract, yet precise way, further compounding the tactility of the imagery.[7] The black and whiteness of the film, by association, invokes a sense of recollection and reflection.

Equally enchanting, mesmerising and hypnotic, Under Darkness and Night Song, transport one from the paralytic statis of insomnia to a place of alchemic transformation, via a constant rhythmic state of ‘ebb and flow’. As one is submerged in the scotopic vision of the night, the haptic visual sensors in one’s brain are tickled and teased by the tactility of velvet blacks and rich pools of lush pigment, which ooze and flow, shimmering as they collide with a watery white tide of resistance. One’s eyes become organs of touch, like fingers they caress the skin of the film as it dissolves away frame by frame. As Juhani Pallasmaa states ‘All the senses, including vision, are extensions of the tactile sense; and all sensory experiences are modes of touching and thus related to tactility’.[8] Although, seduced by the sensory explosion, one is unsettled by the shivering and flickering light that intermittently pierces the frame. As poetic incantations condense out of the shadows in Under Darkness, the continuum of this veiled disquiet, surges and recedes, floating on the breath of every word…

Night Song – film still, 2020

Thoughts fall like raindrops under darkness,

Pooling in puddles and gutters.

An umbrella can’t help,

In such a downpour.

(Words selected from a poem by Rebecca Goldthorpe)

Night Song, on the other hand, engenders a more candid dissidence, as the speed with which the images rush between the frames increases, accompanied by the gyring feverish delirium of an inverted dawn chorus forming a menacing dissonance. Amanda later developed small painting/collages from film stills from Night Song, moving away from the digital screen towards the tangible physicality of painting and drawing. This engagement of hand and mind with texture and surface paved the way for a new set of works about Amanda’s father. Through this more visceral and haptic investigation of her chosen media, Amanda was able to explore her father’s imagination and memories with a profound intensity; ‘touch is the sensory mode that integrates our experience of the world with that of ourselves as the very locus of reference, memory, imagination and integration’.[9]

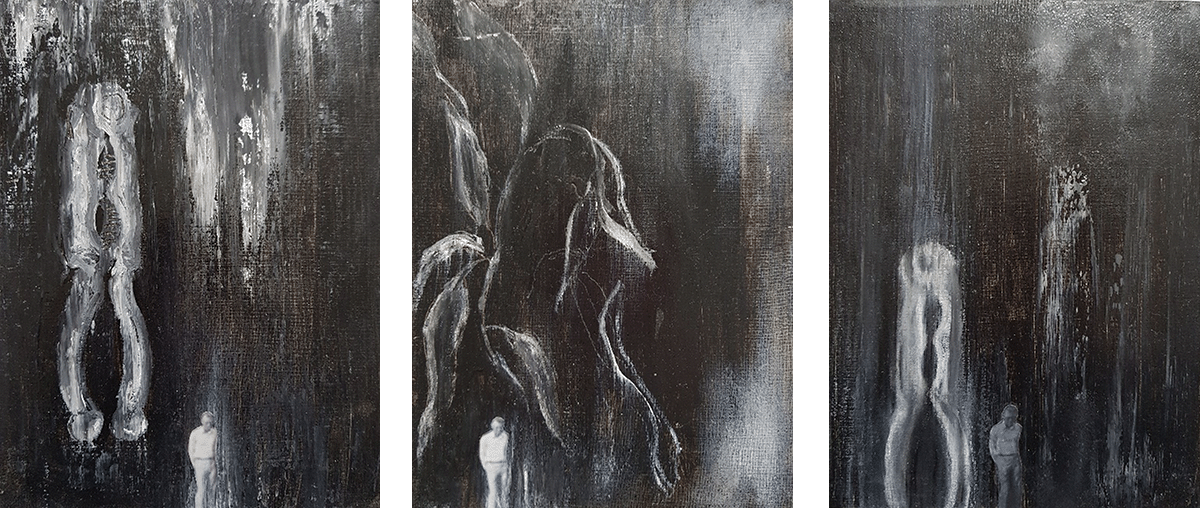

Amanda’s fascination with and explorations of the concept of écorché which informed her very early works remerged in a series of mixed media collages, Albert, 2022, named after her late father. In these images she peels back the layers of his lifetime narrative, in response to his dementia, in the year before he died. Since his death, these small delicate explorations of his thoughts, memories and obsessions have become imbued with a powerful sense of presence in absence. It is as though while making these works, Amanda was unconsciously preparing herself for his loss.

Each image in the Albert series positions Albert himself within a domestic mise en scene, in which his diminutive figure hovers delicately, overpowered by the magnitude of the objects of his obsessions. Larger than life nutcrackers and Carob pods dominate and emphasise the surreal and dreamlike quality of the images. These signifiers that emerge out of the darkness like apparitions reveal the power of Albert’s imagination and the tangibility of his Palestinian childhood memories, as he approached the end of his life. As Esther Dreifuss-Kattan states in her book Art and Mourning: The role of creativity in healing trauma and loss:

The unconscious links past time, the place where unconscious memories are stored in a pictorial archive, to present time, where these visual memories intermingle with thoughts in the present.[10]

As Albert retrieved images linked to memories from his own archive, Amanda used the creative process to mould its content into a tangible and visual form. Perhaps, interwoven into Amanda’s interpretation of her father’s memories are her own feelings about those memories. We are therefore left with a question in our own minds as to what extent our own emotional and experiential conditioning influences how we perceive and interpret the memories of others as well as our own.

References

- Cleveland Clinic, Insomnia (2023) <https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/12119-insomnia#> [accessed 24 June 2023]

- Serpentine Galleries, Map Marathon 2010: Susan Hiller, online video recording, YouTube, 14 January 2016, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p4ylUnYm3Fs> [accessed 7 August 2023]

- Ibid.

- Tate, Art in Focus | Belshazzar’s Feast, the Writing on Your Wall by Susan Hiller, online video recording, YouTube, 3 September 2021, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3Tn7kFzpnYY> [accessed 7 August 2023]

- Laura, U. Marks, The Skin of the Film. Intercultural Cinema, Embodiment, and the Senses (London: Duke UP, 2000), p. 162.

- Ibid.

- Esther, Dreifuss-Kattan, Art and Mourning: The Role of Creativity in Healing Trauma and Loss (Oxon: Routledge, 2016), p. 16.

- Irina Schulzki, ‘Touch and Sight in the Films of Kira Muratova: Towards the Notion of a Cinema of Gesture’, Frames Cinema Journal, 18 (2021), 296 – 298 (p. 296) <https://doi.org/10.15664/fcj.v0i18.2269>

- Juhani, Pallasmaa, The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses (Chichester: John Wiley and Son Ltd, 2005), p. 10.

- Ibid., p. 11.