In November 2021, the painter, sculptor and puppeteer, Jonathan Hayter, exhibited a wide range of works including puppets he designed and made, selected examples of his early shadow puppet/animation projections, sculptures and landscapes. Me and My Shadow show cased Hayter’s creative output from the last two decades of his career.

Me and My Shadow

But still the shadow of the past is cast long into late afternoon,

For golden the apprehension,

Come the end of night….

(Jonathan Hayter, New Beginnings, 2019)

The shadow self, emerges out of the labyrinth of Jonathan Hayter’s unconscious world, sustained by a driving force of performativity which perpetuates a continued exploration of the binary opposition of dark and light. Hayter draws upon an eclectic symbolic and conceptual language of world mythology (Indian, Greek and Egyptian), Jungian and Freudian psychoanalysis and the Tarot, engendering his own form of monomyth (Campbell, 2012). Whilst one could be fooled by the pluralism inherent in Hayter’s work, as a postmodern transgression of master narratives, it transcends the mere folly of recontextualization and reconstitution for the sake of it; asking of its audience a certain level of trust and belief in the dialogue and sincerity of performance, metamodern concerns, which reach beyond the scepticism and irony of postmodernism (Turner, 2019).

Of the four Jungian archetypes of the unconscious; the mother, rebirth, spirit and trickster, it is the mother and rebirth that manifest themselves within Hayter’s key works of the last 5 years – revealed as the ‘dark mother’ associated with life, death, earth, sexuality, and deep transformational energy. Hayter invites his audience to enter the stage of the absent performer in terms of both painting and performance. Since the Renaissance art has come to be understood as the manifestation of the human subject, one of self-imaging which involves a complex interconnectedness of visual representation and concepts of the self (Jones, 2006, pp.2-3). In gazing at the work, we are met with our own gaze, as well as that of the artist’s, which confronts us with our own sense of ourselves not unlike that of psychoanalysis and it is in this sense that Hayter invites his audience to meet their own shadow, as well as his.

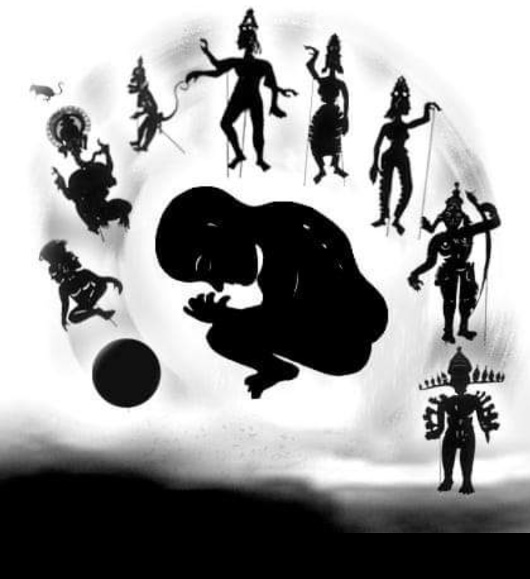

His early shadow puppet/animation projections such as Rebirth from Rama, 2005 (www.figureofspeech.org.uk – puppets and concept: Jonathan Hayter, video

animation: Huw Griffiths and music: J. Hollingsworth) and Moontime, 2005 (www.figureofspeech.org.uk – written and produced by Jonathan Hayter; performers – Jonathan Hayter, Jim Brown, Itta Howie; lighting and video effects: Jonathan Hayter, Jim Brown, Itta Howie; choreography: Jim Brown and video recording: Christiana Numico) immerse the audience in an intimate sensorial entwinement with light, colour and sound; a psychic kaleidoscope of Hindu and Jungian archetypal shapes, forms and figures – namely the mother, rebirth and the moon. The diaphanous layers of living entities that dance, slip and slide as they oscillate between the real and the unreal, the analogue and the digital – simultaneously precipitate and dissolve in the viewer’s conscious and unconscious mind. Through a conflated multisensory sensation, Hayter offers his audience a saturated phenomenological experience. As the Finnish architect Juhani Pallasmaa states “The haptic [touch] experience seems to be penetrating the ocular [visual] …through the tactile presence of modern visual imagery…. we cannot halt the flow of images … an enhanced haptic sensation, rather like a swimmer senses the flow of water against [her/his] skin” (Pallasmaa, 2005, p.36).

However, Rebirth from Rama, and Moontime, are more than just evocative phenomena, they represent the beginnings of a spiritual and psychoanalytical odyssey. Rebirth from Rama, is based on the traditional Bhakti Hindu devotion yogic practices of spiritual enlightenment, practised through the ‘heart centre’ represented by devotion to ‘Mother Meera’, believed to be a divine avatar who receives pilgrims of all religions for darshan, a ritual, where she touches a person’s head, and then looks into their eyes. During this process, she reportedly ‘unties knots’ in a person’s system and permeates them with light, a ritual experienced first-hand by Hayter himself when visiting ‘Mother Meera’. Moontime, exposes the audience to a series of spinning and floating psychedelic Jungian alchemic archetypes, symbolic of spiritual transformation. It explores the idea that the moon is subjected to a different rhythm than the sun, where solar time is ‘mechanical’ and linear, associated with external material matter, whilst lunar time is non-linear and governs the internal emotional realm.

There is a touch of Robert Rauschenberg in Hayter, The Stage is Set, 2021, Soul Engine, 2020 and The Tower, 2021, bring to mind Rauschenberg’s Combine series (1954 –1964) conflating aspects of painting and sculpture, virtually eliminating all distinctions between the two. Hayter’s fascination and delight with constructing imaginary worlds of spectacle and drama has been inspired by the 18th century French-British painter and set designer Philip James de Loutherbourg, whose beautiful Eidophusikon – a large-scale miniature theatre, created the perfect illusion of moving nature: sunrise scenes, sunsets, moonlight images, storms, and volcanoes with sound and music effects, an early form of movie making, achieved by mirrors and pulleys.

Moontime, 2005

In Hayter’s The Stage is Set, Freud meets Loutherbourg as the abandonment of Oedipus by his mother/lover, is brought to life by pulleys, projections and shadows, Jocasta’s face eclipsed by the moon. Left alone on a mountain, his ankles pinned together, Oedipus once free is left with a swollen foot, scarred for life by the trauma of abandonment. It is this abandonment and sense of separation that haunts the work of Hayter in his attempt to heal a wound. The figures that frame the space and form the narrative are created by a process of autosuggestion, where archetypal components by momentary chance association, evoke the genesis and structure of their being. In The Stage is Set, the puppet sculptures come out of the dark and into the light, revealing the wounds of Oedipus. Inspired by the eroticism of the dancing Shivas of the Gupta period (c. 320 – 647 C.E.) they beautifully articulate and twist in opposing graceful arcs, as they are driven by a determined force along a singular plane, towards their fate.

Soul Engine presents a vivid tableau, in a suspended frame of time; the viewer is invited to animate the play upon the stage, set the scene in motion and unravel and reveal the ‘weighing of the heart ceremony.’ The Egyptians understood that a human being is made up of many different parts including the conscious and unconscious and to be a complete human being there is a need for personal growth, but to achieve that personal growth one must go through the darkness into the underworld. The idea was that an individual carried earthly deeds in their heart because it was believed that the heart centre was the place from which human energy emanated, connecting a human being to everything. In Soul Engine, we see Anubis the jackal headed god, god of death, mummification and the underworld, one of a number of gods responsible for weighing the human heart.

On the one side of Anubis, are the scales and the heart and on the other a white feather, which represents the goddess Maat, who was the personification of spiritual truth, justice, and the cosmic order. If the heart weighed heavier than the feather it meant that one still had deeds in this world one had to transcend. There is some evidence that the Egyptians believed in reincarnation, therefore, sitting below Anubis is a crocodile, waiting to swallow the heart, if too heavy with earthly deeds, causing rebirth, until the heart and the feather are equal in weight. As Hayter himself explains, “when you go on the journey into the shadow self what you are trying to do is do what Jung called individuating the personality, which involves absorbing all the extremist parts of the personality that are not serving you or are working against you – the shadow self. The trials and tribulations you are taken on mean that you have to learn to hear with your eyes and see with your ears and think with your heart” (Hayter, 2021).

Hayter weaves a complex drama of parallel sagas, juxtaposing Greek mythology with the foreboding symbolism of the Tarot in The Tower, 2021, which presents its viewer with an enigmatic impending existential dilemma. It is both the tower where Daedalus was imprisoned by King Minos of Crete, and the tower of the Tarot, itself a solid structure, but built on shaky foundations, it only takes one bolt of lightning to bring it down. It represents ambitions and goals made on false premises. Just as Daedalus’ son Icarus, flies too close to the sun and melts his wings due to his own foolishness, the fragility of the tower of misguided intentions is precariously held together by the counterweight of the conscious ego, pivoting on a lunar axis controlled by lunar cycles, it is about to be demolished by divine intervention. The audience is met with an abandoned site of alchemic ritual, inscribed with the indexical trace of trauma rendered present in its absence. Like a giant Jenga totem, about to tumble, it teeters on the edge of collapse, the abyss of darkness and chaos awaits its demise, as the hubris of the Anthropocene is about to meet its end.v

While the shadow theatre and sculptural works explore the inner workings of the psyche and collective unconscious, Hayter’s paintings have taken him on a more external trajectory towards and within the landscape. Rejecting the ahistorical Cartesian model of ‘looking at’ the world as a disinterested and disembodied subject, Hayter immerses himself within the Cornish landscape, in particular the bewitching and embracing primeval Penwith peninsular; in his words a place and space in which to ‘heal’.

As the French philosopher Merleau-ponty states in his last published essay Eye and Mind, 1961, “It is by lending [her] his body to the world that the artist changes the world into paintings. To understand these transubstantiations, we must go back to the working, actual body – not the body as a chunk of space or a bundle of functions but that body which is an intertwining of vision and movement” that which is the “flesh of the “world” (Merleau-ponty, 1969). As Hayter himself declares in the words of Alan Watts, “Our fundamental self is not just inside the skin it is everything around us with which we connect. When you look out of your eyes at nature happening out there you are looking at you” (Watts, 1971). The scale and the visceral nature of Hayter’s evocative Landscapes, form an emotional interface where inner and outer worlds meet to forge a chiasma, such that he inscribes his substrate with an unmediated expressionism.

As the French philosopher Merleau-ponty states in his last published essay Eye and Mind, 1961, “It is by lending [her] his body to the world that the artist changes the world into paintings. To understand these transubstantiations, we must go back to the working, actual body – not the body as a chunk of space or a bundle of functions but that body which is an intertwining of vision and movement” that which is the “flesh of the “world” (Merleau-ponty, 1969). As Hayter himself declares in the words of Alan Watts, “Our fundamental self is not just inside the skin it is everything around us with which we connect. When you look out of your eyes at nature happening out there you are looking at you” (Watts, 1971). The scale and the visceral nature of Hayter’s evocative Landscapes, form an emotional interface where inner and outer worlds meet to forge a chiasma, such that he inscribes his substrate with an unmediated expressionism.

Uninterested in the conceit of formulaic tricks, Hayter discards technique amidst a psychic battle in which he wrestles with the shadow self in the pursuit of a reconciliation. His studio paintings are the expression of a raw and undidactic dialogue with the materials themselves; chaotic and questioning, through trial and error they are the manifestation of a gestural, performative ritual. Embracing chance and happenstance, Hayter submerges himself in a frenzied dance of free association with texture, colour and tone. As in the words Jiro Yoshihara (founder of the Japanese art movement Gutai (embodiment) “When the material remains intact and exposes its characteristics, it starts telling a story, and even cries out…. When the individual’s quality and the selected material melt together in the furnace of automatism, we are surprised to see an emergence of a space unknown, unseen and unexperienced. Automatism inevitably transcends the artist’s own image” (Yoshihara, 1956, cited in Jones and Warr, 2006, p.194).

References

- Campbell, J. (2012) The Hero with a Thousand Faces. 3rd Edn. California: New World Library.

- Hayter, J. (2021) ‘Studio Dialogues’. Interview by Rachel Hindley, 24 October.

- Jones, A. (2006) Self/Image: Technology, Representation and the Contemporary Subject. London: Routledge.

- Jones, A. and Warr, T. (Eds) (2006) The Artist’s Body. London: Phaidon Press.

- Merleau-ponty, M. (1969) The Visible and the Invisible. Illinois: Northwestern University Press.

- Pallasmaa, J. (2005) The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses –.

- Turner, T. (2019) Garden Design and Landscape Architecture. Available at: https://www.gardenvisit.com/blog/author/tom/ [Accessed: 16 November 2021]

- Watts, A. (1971) ‘Alan Watts: A Conversation with Myself – Part 1’, Essential Lectures 12: Conversation with Myself. Available at: https://www.organism.earth/library/document/essential-lectures-12 [Accessed: 23 November 2021]